Wednesday, December 5, 2018

A sermon on John 6:53-63

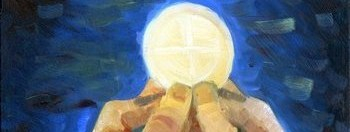

In reading the Gospels, it can often be easy for us to playfully mock Christ’s disciples when they seem to ask stupid questions of him, or miss his point on core theological issues. But I think I can speak for a lot of folks in saying that I find myself sympathetic to the disciples in this passage as they question Jesus again on his teaching concerning the Eucharist and the physical consumption of his body and blood. “This teaching is difficult,” they say. And indeed it is! Debates about sacramental theology aside, there is something very challenging in what Christ is saying here, and in his repeated assurance that no, he is not speaking metaphorically about his flesh and blood.

By forcing the Church to grapple with the literal physicality of his presence on Earth and in the Eucharist, Christ in this passage compels us to consider and struggle with the religious implications of human physicality and embodiment, and the connection of our physical and spiritual selves. These implications can trouble hegemonic, and often sexist and heterosexist, Church teachings that place the physical or bodily realm of “temptation” or “impurity” below the spiritual realm of abstract theology.

An example of the way Eucharistic imagery and theologies of embodiment can challenge the Church’s fabricated binary can be found, surprisingly, in medieval Europe; specifically, in the writings and experiences of medieval women mystics. For my Christian Mysticism class, I am currently working on a project that focuses on female Eucharistic devotion in the Middle Ages — an interesting and well-documented trend. Through my research, I have found that mysticism in general, and Eucharistic devotion specifically, often provided pious medieval women the opportunity to achieve spiritual agency in the context of the patriarchal church, which systematically devalued them and their bodies as impure and outside the realm of religion. I learned that many of the women utilized devotion to the Eucharist in particular as an exercise in female embodiment and conceptualizing the embodied feminine nature of the divine. By experiencing Christ as suffering flesh to be consumed, the female mystics were able to envision God as an image or reflection of themselves and their daily life and work as women – bleeding, laboring, nurturing, and breastfeeding. As the women’s bodies broke and bled in labor and delivery to bear children into the world, they saw in the Eucharist Christ’s own body breaking and bleeding on the cross to deliver humanity to salvation and bring new life. As they fed their children with the food and milk of their bodies and breasts, they saw in the Eucharist Christ feeding humanity with the blood from his side.

Whether considering the female character of Christ’s physical life and death appeals to your sensibility or not, there is something to be said for considering the role and importance of embodiment in the Christian life. As we move through Advent and approach Christmas, we have the opportunity to reflect upon the profoundly incarnational aspect of our faith: that God took a body, was delivered by way of Mary and delivered us by way of the Cross, in and through flesh and blood. Though Christ resurrected has ascended to Heaven, we still speak of his body as the Church, in which the Spirit makes her home and does her work. The female mystics of the Middle Ages, and more contemporary feminist and womanist theologies, encourage us to recognize and experience Christ in our own embodied lives: in our daily work, in our physical suffering and comfort, in our hungering and being filled, in our overwhelming physical experiences of joy and despair. They encourage us to reject theologies that elevate “the spiritual” over the bodily and that understand Christ’s teaching on the Spirit giving life and the uselessness of flesh as a rejection of embodiment. Instead, they encourage us to see Jesus’ instruction in this reading, and his reassurance to the disciples concerning spirit and flesh, as suggesting, not hierarchy, but a theology of integration: that body and spirit cannot be separated and are properly experienced as united elements of God’s human creation – Spirit working through flesh.

Thus, as we take communion this evening and feed on Christ in body and Spirit, let us remember and celebrate that the Eucharist is, at its core, an exercise in embodiment. Let us practice how it feels to physically and bodily experience the palpable love of God.

Amen.